PUBLISHED NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2018

by John Parsons, Writer/Consultant at IntuIdeas --

John Parsons

AP connections are getting easier, but book publishers need to ask questions before adopting it.

Book publishers, authors, and their readers live in a world where print is only one of many, many ways we communicate with other humans. Since the invention of the telegraph in 1833, books have had to coexist with a growing array of near-instantaneous, electronic alternatives.

The question today is the same as it always has been: Do new media only compete with printed books, or can they work with Gutenberg's centuries-old invention? One way the latter might be true is through the digital medium of augmented print, or AP.

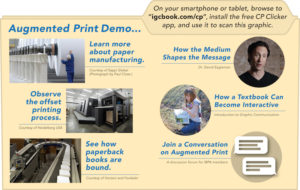

Augmented print is comparable in many ways with augmented reality (AR), which many conflate—incorrectly—with its more ambitious cousin, virtual reality (VR). VR's advanced software, expensive headsets, glasses, gloves, and full-body suits may hold promise for training and gaming applications but are well outside the realm of publishing. On the other hand, neither AR nor AP require special hardware, only a smartphone or a tablet. Broadly speaking, AP includes any interaction with print that triggers or facilitates an online, typically mobile experience.

Augmented print began some time ago, with URLs or email addresses placed on a business card or brochure. Later, it included the ostensibly more convenient QR Code approach, which linked the printed surface to a single online destination. More recently, AP began using printed watermarks or image recognition to trigger online mobile activity. One such technology,

Ricoh's Clickable Paper, provides access to multiple online or telephonic events based on a unique, recognized "zone" on a printed page—even a page printed years or decades ago.

Is It Right for Publishers?

Recently, the AP "bridge" between print and mobile has improved significantly. Both Apple and Google recently added QR Code recognition to the iOS and Android native camera app (finally achieving parity with Japan), and more advanced AP connections are coming soon. But just because it's getting easier, book publishers need to ask questions before adopting it.

The first question is easy but often overlooked by both AP and AR enthusiasts: Does the printed component have lasting, intrinsic value? Marketing brochures—a typical use case for QR Codes and more advanced AP—have a very short "half-life." Recipients may keep them only for a few days or even less, making it unlikely they will bother to scan. Printed books, on the other hand, have much greater longevity. They also have a haptic advantage over their electronic counterparts, as legitimate

scientific studies have shown. If a book is valued for its own sake, then it is potentially a candidate for adding AP or even AR functionality.

The second question is trickier: Does the AP component complement the book reading experience, or does it merely distract from or attempt to replace it? The answer will depend on the type of book being considered. Depending on the genre, trade fiction may benefit from auxiliary video content (e.g., author interviews, trailers for upcoming movies based on the book), but the most common AP use case will probably be a more convenient connection to the author's or publisher's social platform.

Trade nonfiction has more AP potential, not only for updates and supplemental reading but also for interactive mobile experiences. A travel guide, for example, would benefit from a customized GPS itinerary—based on a specific section of the book combined with the reader's individual interests. Cookbooks would benefit from demonstration videos, downloadable lists of ingredients, and even store locations where they can be found. Children's books would benefit from readalong audios and possibly links to e-learning supplements.

Perhaps the greatest potential for AP and books is in the fields of K-12, higher education, and vocational training, as the example in this article illustrates.

A third critical question is: How can users' reluctance to download a separate AP app be overcome? This was one of many reasons why QR Code adoption failed outside Japan, where mobile phones included built-in reader software. The answer is twofold. Eventually, mobile devices will include greater, built-in AP capabilities. Scanning an object or a page will, over time, become a more normal behavior for mobile users. Until then, however, the most successful strategies for books will be those where publishers add AP scanning capabilities to their own, existing mobile apps. Readers usually need more than one reason to download and use an app. AP should be only one of many such reasons.

Finally, there is the question of cost. Can book publishers afford to add AP-connected content and interactivity in an already cost-constrained business? If the mobile content consists of many new, professionally produced videos or animations, then the answer is probably no. However, if editable video already exists, or can be easily produced or licensed, the prospects are better. Also, keep in mind that many types of mobile interaction do not require original content, such as discussion forums and social media groups. An AP "bridge" is simply a more convenient way to access existing resources.

A Textbook Example

To attempt to prove the AP thesis, this writer undertook an ambitious project with Cal Poly Professor Emeritus Harvey Levenson. While updating the 2007 textbook,

Introduction to Graphic Communication, the idea occurred to link the book to demonstration videos, commentary, and other material. Rejecting the use of QR Codes, the authors ultimately partnered with Ricoh USA and their Clickable Paper technology to publish our "multi-book" in April 2018.

The book's video content was curated from a wide variety of sources—some clearly identified as promotional. Permissions were obtained, and the edited results were hosted in a secure, online video portal donated by

Viddler. The quality of the videos varied widely, but the overall mandate—to help students understand technology that their schools could not afford to own—was followed.

The book and its online component have been widely adopted by graphic communications educators, including Ryerson University, Arizona State, and Bowling Green, with others (RIT, Cal Poly, Clemson, and others) poised to do the same. Printing companies—including some of the world's largest—are also planning to use it for internal training.

The Bottom Line

Book publishers have a decided advantage over other graphic communicators when it comes to augmented print. Their printed product is potentially more long-lasting and valued than magazines, newspapers, and marketing collateral. The right augmented print experience, coupled with the right kind of book, can add significant reader value. For publishers and authors who want to exceed expectations and differentiate their work, AP is a technology whose time has come.

Former Seybold Publications editor John Parsons, of Seattle-based IntuIdeas, writes and consults on a wide range of printing and publishing-related topics. He is the co-author of Introduction to Graphic Communication

, a comprehensive overview of the art, science, and business of print. It is the first textbook to utilize Ricoh's Clickable Paper as an augmented print "bridge" to related video and other interactive mobile content.

To learn about the future of publishing, check out this

IBPA Independent article, "

AI and What it Means for Publishing."