PUBLISHED OCTOBER 2017

by

Deb Vanasse, Reporter,

IBPA Independent magazine --

Deb Vanasse

More independent publishers should consider licensing arrangements as an alternative revenue source, as the returns can be significant.

Amid the everyday challenges of acquisition, production, and marketing, publishers may overlook a significant revenue stream: the licensing of content.

"Books are the headwaters of the intellectual property Nile," says attorney Lloyd Jassin, co-author of

The Copyright Permission and Libel Handbook. "Many publishers stay close to the headwaters. [But] 50 percent or more of the profits can be downstream licensing deals."

Returns from licensed content can be significant. "Depending on the type of licensing, publishers can see increases in revenue within a year or by tenfold within a few years," says MJ Courchesne, owner of Gryphon Publishing Consulting. "Licensing also offers the benefit of reaching audiences that a publisher might not normally reach, thereby increasing awareness of the brand."

Know the Terms

Through licensing arrangements generated by a single title, publisher Rod Colvin estimates that Addicus Publishing boosted its bottom line by $500,000. So why aren’t more publishers pursuing this alternative revenue source?

One reason is lack of understanding, Colvin suggests. Before they can successfully pursue licensing deals, publishers need to understand the relationship between trademark, copyright, and licensing. They need to differentiate between assignment and licensing, and between exclusive and nonexclusive rights. They also need to understand the two directions in which licensing works.

Like trademark, copyright is a type of intellectual property, explains publishing attorney Jonathan Kirsch. Trademark protects words and symbols indicating the source of goods and services, while copyright protects works of authorship.

“Both kinds of intellectual property can be assigned or licensed,” he says. “An assignment conveys ownership of the intellectual property, and a license conveys only the right to use the intellectual property on stated terms and conditions.” Because assignment transfers more legal rights, publishers tend to seek assignment of copyright when they acquire content.

But other publishing agreements tend to be drafted as licenses, Kirsch notes. "A good example is the licensing of translation and foreign publication rights by a US publisher to a foreign publisher, which are almost always licensed for a specified term of years, in a specified language, and a specified territory," he explains. "Another example is the granting of permission to use photographs, artwork, and quotations from a previously published work, all of which are usually limited in various ways."

Licensing happens in two directions—in and out, explains Roy Kaufman, managing director at the Copyright Clearance Center and author of

Publishing Forms and Contracts. When licensing in, publishers acquire permission to use copyrighted material. To license in, publishers typically expend capital in order to use and market content. To license out, publishers market acquired rights to others for use in their own ventures.

Granted to a single user, exclusive rights are more valuable than nonexclusive rights, which may be granted to multiple users, notes Jassin. That is why publishers seek exclusive rights to manuscripts, and it’s why the most lucrative licensing-out arrangements involve exclusive rights.

As Barry Rubin of Messianic Jewish Publishers explains, publishing professionals may be better positioned than the original rights holders to generate revenue through licensing. “Because of the complexities of finding rights customers, getting rights contracts signed, keeping track of numbers and sub-licensing to others, plus avoiding any conflict of interest between other authors, it makes a lot of sense to let the publisher handle these matters for the author,” he says.

Value in, Value Out

In producing a book, publishers convert rights into products that generate revenue. But the rights themselves—licensed in, licensed out—also have value.

In licensing out proprietary digital content, Kaeden Publishing generates income from “very little investment,” says president Craig Urmston. The company also benefits from licensing-in arrangements. By licensing print and digital rights as well as English co-printing rights from foreign publishers, Kaeden Publishing has added low-cost content that had effectively doubled its list.

Other publishers use licensing-out to reach special sales markets. In a move that was part of her business plan from the start, publisher Mary Schafer of Word Forge Books licensed rights to print, distribute, and sell a special customized version of

Metal Detecting for Beginners: 101 Things I Wish I’d Known When I Started to a company that makes metal detectors.

“I contacted the manufacturer of the detectors I use most to see if they’d be interested, and one of them was,” she explains. “All I had to do was spend about three hours doing a new cover shoot, producing the new cover, and changing the title and copyright pages. The licensee takes care of all printing and distribution costs, and I just sit back and cash a very good-sized check about once a quarter.”

Divorce in Nebraska, by Angela Dunne and Susan Ann Koeing

At Addicus Publishing, publisher Rod Colvin has entered into multiple licensing arrangements for a single title,

Divorce in Nebraska: The Legal Process, Your Rights, and What to Expect. Noting that much of the book’s content could be used in other states, Colvin launched a direct mail campaign, reaching out to attorneys across the nation with an author services proposal that included licensing out the right to reprint much of the book’s contents.

“We offered them the rights to

Divorce in Nebraska with the understanding that they would need to customize the book to fit the laws in their states,” Colvin explains. “One big selling point to potential authors was that having the rights to the Nebraska book took about 200 to 300 hours of work off their desk—they could use our book as a template rather than start from scratch.”

In his pitch, Colvin pointed out the book’s marketing potential, elevating the attorney-author’s professional profile while also garnering media attention. The licensed rights are exclusive by state, ensuring that each author customizing the material to their state could avoid competition from others doing the same.

The payoff has been huge. To date, Colvin says the licensing out of rights to

Divorce in Nebraska has generated approximately half a million dollars in revenue.

The Fine Points

Before entering into a licensing agreement, publishers do well to seek advice from experienced professionals. “Negotiating contracts for the sale or license of rights is complicated,” Jassin says. “Not only is there the sometimes-thorny issue of who should control the rights, but each species or type of right—volume, audiobooks, foreign translation, film/ television, dramatic, merchandise licensing, etc.—has its own complexities.”

As a crucial starting point, Kaufman urges publishers to make sure they hold the rights they intend to license. “There have been a lot of lawsuits against publishers who got permissions to use, say, artwork and didn’t pay attention to scope of the licenses in,” he explains.

When drawing up licensing agreements for

Divorce in Nebraska, Colvin addressed this step first. His attorney drew up a contract with the author who retains copyright to the original book, stipulating that she allows the content to be used as part of a template for books that address divorce in other states.

“If the parties agree on a license, it is very important to draft and sign a licensing agreement that describes in detail how the rights are being licensed,” says Kirsch. A licensing agreement often limits the use of rights to a specified territory, language, medium, format, time period. It also includes terms of payment. Use of online templates may result in contract language that’s outdated, inapplicable, and unfavorable to a publisher’s interest, Kirsch warns.

Schafer affirms the value of a written agreement. “I’m amazed at the number of small publishers who still work on a handshake only,” she says. “The minute you do that, you immediately show yourself to be an amateur just waiting to get taken advantage of, and indeed, open your company up to losing a lot of money and potentially some publishing rights.”

Attorneys help ensure that a proposed license agreement is legally appropriate, says Kaufman. Literary agents can advise clients on the value of certain licenses, such as film options. A licensing aggregator acts as a clearing house and intermediary. Kaufman’s firm, Copyright Clearance Center, connects corporate and academic clients seeking to license rights with publishers “big enough that people might be looking for you.” Courchesne’s Gryphon Publishing Consulting helps publishers evaluate the licensing potential of their properties and assists publishers with licensing in rights from copyright holders.

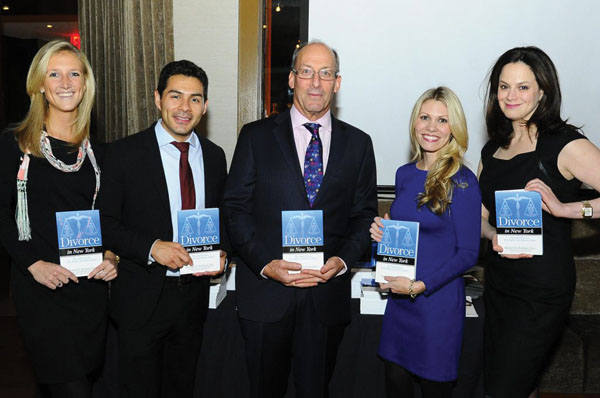

David Stuttman and colleagues celebrate publication of Divorce in New York

Assess the Potential

As Courchesne points out, licensing is a potentially lucrative way for publishers to increase brand awareness, not to mention revenue. But when it comes to licensing, not all titles are created equal. And as with all assets, it’s crucial to know the market.

Kaufman advises publishers to be proactive in their pursuit of licensing arrangements. “There are places where you can list subsidiary rights, corporate reuse rights,” he says. “But what you actually have to do is market your work. Find works similar to yours. Where do those works sell?”

Properties that generate strong market interest are the best candidates for licensing out, says Courchesne. A product that represents an established brand or a timely message will benefit from the increased exposure.

Outside of niche markets, Schaefer notes that nonfiction likely has more licensing potential than fiction. “But it really does depend on your own imagination and creativity in approaching the subject matter and the potential licensee,” she says.

In pursuing licensing arrangements, independent publishers tap assets that require no stocking, no inventory, no distribution. By understanding the terms, assessing the value, and attending to the fine points, they can make the most of this alternative revenue source. ⦁

Co-founder of 49 Writers and founder of the author co-op Running Fox Books, Deb Vanasse is the author of 17 books. Among her most recent are Write Your Best Book,

a practical guide to writing books that rise above the rest, and What Every Author Should Know,

a comprehensive guide to book publishing and promotion, as well as Wealth Woman: Kate Carmack and the Klondike Race for Gold.