PUBLISHED NOVEMBER 2017

by Matt Knight, Author,

THE GENE POOL --

Matt Knight

Truth is stranger than fiction. It is an old adage that, for writers, equals entertainment. Maybe the story is uplifting or heroic, sad or horrific. Maybe the story is a retelling of noteworthy events, a glimpse into the private lives of public figures, or a compelling dramatization of a private citizen’s life. Whatever the subject matter, choosing to write about facts and events involving others brings with it significant legal risks that must be analyzed for legal clearance and the necessary permissions and acquisitions of life story rights (regardless of whether the literary work is a biography, memoir, screenplay, or fictionalized true story from the writer’s own life or someone else’s). If not, the writer and publisher might find themselves the recipients of a cease-and-desist letter, or worse, the defendants in a lawsuit.

What Are Life Story Rights?

Life story rights are a collection of legal rights held by an individual regarding a story about someone’s life. The purpose for securing these rights or the permission to use the facts of someone’s life is to protect the writer and publisher from being sued for defamation, invasion of privacy, or the misappropriation of the right to publicity. Life story rights agreements, depending on the breadth of the contract language, allows the writer to use and potentially change or dramatize the life story for entertainment purposes (whether in print or on screen).

The Legal Principles of Life Story Rights

1. Defamation

We usually hear the legal term “defamation” when a gossip rag damages a celebrity’s reputation by printing false rumors of a derogatory nature like a sexual escapade, or an ex-paramour’s heroine addiction. But defamation in literary work happens too, usually in memoirs and nonfiction. Thankfully, for writers and publishers, the success rate for defamation suits tends to be low. Even so, no one wants to spend time and resources in court.

Defamation covers two torts: libel and slander. Libel is the publication of a false statement that injures a person’s reputation (as opposed to slander, which covers the verbal form of defamation). A libelous statement must be false and factual. The defamed person must be living and need not be identified by name. The real person need only be identifiable to readers via the information provided. Business entities and small identifiable groups (like a lacrosse team) can be defamed too.

If you find yourself subject to a claim of defamation, your best defenses would be truth, opinion, or parody/satire.

- Truth is a complete defense to a defamation claim. No false statement equals no libelous statement. Even if minor inconsequential facts are incorrect, libel does not exist if the overall statement is true.

- Opinions are protected (because opinions are neither true nor false). This defense, however, can be tricky to navigate. Just because you say it is your opinion will not keep the statement from being defamatory. Merely implying a false statement can be enough. “In my opinion, she is an alcoholic” is just as defamatory as “she is an alcoholic.” These issues often arise with memoirs and biographical works. The best way to utilize this defense is for the writer to provide in their work the underlying facts on which the opinion is based, like, “She was convicted of a DUI, and then went to rehab.”

- Parody and satire genres exaggerate material for comic effect, which is not considered to be true or a statement of fact.

These are defenses, which means you use them after you have been sued. Instead of relying on a defense, do your best to avoid a libel claim before you publish.

2. The Right of Privacy

People have the right to be left alone. Privacy is invaded when private facts not in the public’s interest are publicly disclosed. While the truth can deflect a defamation claim, often the truth when disclosed can be the basis for an invasion of privacy claim.

Usually, invasion of privacy occurs when:

- Private facts that are not of public interest are disclosed;

- There has been intrusion into a person’s private life; and

- Someone is portrayed or misrepresented in a false light, i.e. highly offensive to a reasonable person.

The injured person must be living (unless you want to dig up the casket, which is an invasion of another kind). The disclosure of private facts must cause harm to the person’s reputation (personal or professional). Mere embarrassment usually is not enough. The injured person must have a reasonable expectation the disclosed fact was to remain private. So, if facts occurred in a public setting, then most likely there is no expectation of privacy.

Often the most crucial point in a right to privacy claim is whether the disclosure was of public interest. Fortunately, writers have had luck in persuading courts that the disclosure of private facts is of public interest when it illuminates the human condition. Likewise, a memoirist is given leniency for disclosure of facts in their own story, even though it might be private facts inextricably intertwined with a third party. But a third party telling someone else’s story about a child born from an incestuous relationship that was never made public and the crime never reported has been held to violate the right of privacy. The facts were newsworthy, yet revealing the identity of the victim was not a matter of public interest.

3. The Right of Publicity

Misappropriation of the right of publicity is using someone’s name, likeness, or identifying characteristics for advertising, merchandising, endorsements, promotional, or commercial purposes without permission. The law normally applies to the living, although some states will extend the right of publicity posthumously. And it only applies to a person who makes money from who they are (i.e. famous people).

If you do not have permission, do not use someone’s name or likeness for commercial purposes. Just because you spilled a cocktail on Liza Minnelli once at a party, you would not put her picture on the cover of your memoir to boost sales. But, if you have written a biography, screenplay, or news article about a famous person, permission is not required because the right of publicity yields to the First Amendment.

Likewise, you would not add Lee Child’s endorsement on your book if he has not given one. Nor would you claim an unauthorized biography of Madonna was authorized. Use common sense—no taking advantage of their reputation for commercial purposes without permission.

And, of course, a real person, famous or not, can make cameo appearances if you stick to the facts that are in the public domain.

When to Secure Life Story Rights

Depending on whose story is the subject of the literary work, a writer may need to own or seek permission to use those life story rights or the story rights of any ancillary individuals involved, even if they only figure marginally in the story.

Here are a few questions to consider when making that determination.

Is the life story yours or someone else’s?

If it is your story, the First Amendment allows you great latitude in telling it. But be cognizant of not invading the privacy of others involved in your life story. You may need permission to use facts involving third parties like lovers, siblings, or friends if the private facts would be highly offensive. If you are writing about someone else’s life story and the person is not a public figure, you may need to secure a life story agreement unless the story can be told using facts from the public domain, like news articles and court transcripts.

Is the subject of the life story dead?

If so, you are in luck. As noted above, the right to sue for defamation or invasion of privacy stops at the grave (feel free to spread as many lies or reveal as many secrets as you like). While the dead cannot suffer reputational harm, however, the right of publicity may extend to one’s heirs depending on the state. Be careful not to defame someone related to the dead; the wife of the dead man you claimed was head of a family-run meth lab may bring her own defamation suit.

Is the subject well-known?

Public figures and celebrities usually have trouble proving invasion of privacy because their lives are of public interest and there is less expectation of privacy. That is life in the spotlight. For example, Elizabeth Taylor failed to stop an unauthorized television biography of her life because the court held the biography was of interest to the public.

Is the event newsworthy?

Again, public interest tends to yield to the First Amendment, meaning courts typically give latitude to stories that are newsworthy. However, a person still might sue if they can prove they have been defamed. If the event or facts are not newsworthy, consider fictionalizing the true story.

How to Avoid Being Sued for Violating Someone’s Story Rights

- List the people who are living or dead, who are famous, public, or private individuals. Are your characterizations of these people, or the story events involving these people, negative or favorable? If favorable, your chances of being sued are fewer. Remember, your idea of what is considered favorable may differ from what others consider to be favorable. If negative, then these will need closer legal inspection.

- List the facts and scenes that might be objectionable. Are the facts or events you are writing about private, public, or newsworthy? Again, what you believe to be public or newsworthy may be different from what others believe to be public or newsworthy. Private facts demand closer scrutiny.

- List the facts that need verification, the people who need interviewed, and the people who must sign permissions and releases.

- Keep records of your research. Record interviews. If you are writing a memoir or a biography, document your fact-finding and keep copies for proof that you have not made negligently false statements. Tape recordings are the best when interviewing. Next to that, contemporaneous notes are helpful (all of which should be dated and signed, and the place and source identified).

- If you think readers will recognize the real person in your literary work who might have a legal claim, reduce your risk by layering in as many fictional details as possible to distance the character from the real person. Change the person’s sex, ethnicity, name, residence, age, physical traits, odd quirks, personal background, familial connections, profession, friends, time, setting, etc. Or create a composite character molded from a variety of people or events. The problem arises when the writer does not disguise enough so the connection between character and real person is easily linked, or they wrongly assume the real person will not consider their statements defamatory or disclosures an invasion of privacy. Just be aware that changes will not always shield a writer from liability.

- Use common sense. As tempting as it might be, do not use your novel as revenge. That is asking for legal trouble.

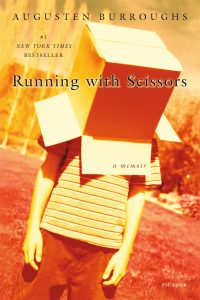

- Use a disclaimer or a nicely written acknowledgement. But remember, disclaimers are not full proof. In 2007, Augustine Burroughs settled a defamation suit filed by a family depicted in his memoir Running with Scissors. He agreed to call his literary work a book instead of a memoir, and acknowledge that certain real families portrayed in his book might have memories of the events that differ from his. While disclaimers that acknowledge certain names and places have been changed can help, it may not prevent readers from identifying the real person who is the subject of the defamatory statement, and often will not shield a writer from liability.

- Retractions can be useful under the right circumstances, but do not rely on these. Some states have retraction statutes, but these generally apply to newspapers, radio stations, and magazines. There are a few cases that involve online defamatory statements and the use of retractions to minimize damages. Retraction statutes do not generally apply to book publishers and could, if used, be considered an admission that the statement was false and defamatory.

- Consult a lawyer to vet the manuscript and provide advice on how to minimize risk. If you are traditionally publishing, use your publisher’s legal department; if self-publishing, hire your own publishing lawyer. A lawyer will explain what is acceptable and what is not, and will draft an agreement with the appropriate provisions to secure ownership of life story rights.

[caption id="attachment_25335" align="alignright" width="200"]

Running with Scissors, by Augusten Burroughs

Understand that negotiating these agreements involves competing interests between you and the subject of the story. The biggest item you are hoping to secure is a release from being sued for defamation, invasion of privacy, or misappropriation of the right of publicity. Depending on your project, you may want the subject’s or a third party’s cooperation. You may want access to personal materials, like photos or journals. Some projects demand the need for exclusive rights to the material so others cannot produce or create competing literary works. Other projects require more flexibility in how the real person is portrayed and the story embellished and dramatized.

If your literary project is based on real-life events or someone’s life story, a little upfront organization and legal scouring will save you hassles in the long run. The last thing you want is for your creative work to meet an untimely death from not securing the proper permissions and life story rights prior to publication or release.

The Residuum Trilogy.