PUBLISHED MARCH/APRIL 2018

by Deb Vanasse, Reporter,

IBPA Independent magazine --

Deb Vanasse

To win at the news game, publishers need to craft newsworthy angles, strategically pitching stories that focus less on the book and more on the content journalists seek.

To its own author and publisher, every book seems like news. After all, the effort to create, publish, and market a title feels monumental. Shouldn’t the world take note? In truth, what makes news is altogether different. To win at the news game, publishers need to craft newsworthy angles, strategically pitching stories that focus less on the book and more on the content journalists seek.

What’s News?

Terry Filipowicz

With an extensive background in journalism, public relations, communications, and TV news, Great Potentials Press Vice President Terry Filipowicz is exactly the sort of person a publisher wants in charge of getting its titles and authors into the news cycle. But to get media coverage, publishers don’t have to employ news gurus. What matters, says Filipowicz, is that publishers pay attention to

six news values: 1) importance or significance, 2) prominence, 3) conflict, 4) human interest, 5) timeliness, 6) and proximity.

A story need not have all six news values, she says, but publishers do need to objectively weigh the stories they intend to pitch against the values journalists want. “Publishers and authors sometimes perceive their book or themselves as inherently newsworthy,” she says. “The hard, ugly truth is that, in general, we’re not.”

Addicus Books publisher Rod Colvin also brings journalistic experience to his work in publishing.

As news director of an Omaha, Nebraska, radio station, he received hundreds of news releases weekly. “I developed a sense of when something was newsworthy and how to pitch a news story,” he says. He now uses this intuition to pitch stories tied to books on the Addicus list.

Colvin drew media attention to

Divorce in Illinois by working the news values of importance, timeliness, and proximity. The book came out in the first quarter, coinciding with a trend the company discovered by doing some basic research: Because people don’t like to break up during the holidays, divorce filings pick up in January and peak in March.

Colvin pitched this angle with a local tie-in—“Divorce Rates Expected to Peak in March. Illinois Attorney Explains Why.” After an explanatory lead-in, he quoted the book’s author on why rates peaked at that time of year as well as how divorce rates were changing.

The pitch led to a 20-minute author appearance on a WGN Chicago Sunday morning television program.

“It’s one of the largest TV markets in the nation,” Colvin says. “Buying such time on the air would have cost tens of thousands of dollars.”

Timeliness is an especially important consideration for publishers, Filipowicz says. “Is it the Christmas holidays and you publish knitting books? Send a pitch about making the perfect snuggly holiday gift,” she suggests. “Is it a British royal wedding and you wrote a novel about kings and queens that took inspiration from the British royalty? Send a pitch.”

Make the Pitch

Local media is

easiest to pitch, and it has the built-in news value of proximity. In choosing which outlets to approach, Filipowicz reminds publishers that not all media are created equal. “Your local pop music station more than likely doesn’t provide news,” she says. “It just provides Taylor Swift’s newest song. So take a look or listen to your local media before pitching.”

She points out that some local TV stations feature “lifestyle shows” consisting almost entirely of interviews. “They aren’t produced out of the newsroom,” she explains. “It’s a whole separate team because the shows are sales and marketing.” Unless you’re a nonprofit or you’re talking about a local event, you’ll likely be asked to pay a fee for being hosted on such shows. Filipowicz suggests teaming with a nonprofit if there’s a good fit—for instance, a representative from a local animal shelter talking on air with the author of a book about pets.

To pitch beyond local markets, Colvin notes that you can purchase lists from services such as

cision.com that include contacts in television and radio news as well as bloggers and editors of news print, magazines, and trade journals. “For a statewide story, we will send our news release to several hundred editors and producers,” he says. “If the book and story have national appeal, we’ll send the pitch out to thousands of editors.”

Personal contacts can be helpful, but Filipowicz advises publishers to be prudent in working them. “I have a lot of contacts in national TV news, but I’m incredibly careful about what I pitch them and how often I directly contact them,” Filipowicz says. “I don’t want to take advantage of relationships.”

Colvin and Filipowicz both recommend pitching by email rather than by phone, US mail, or in person. “Send the press release or pitch embedded in the email as text,” Filipowicz says. “If it’s a press release, also attach it as a document.”

Reaching out through social media can also be effective. “While in the newsroom, I received a good number of people contacting me via Facebook personal message,” Filipowicz says. Best practice, she says: Keep it brief.

When drafting a pitch or news release, Filipowicz advises publishers to start with what’s interesting and timely, then tie in the author as an expert on the topic. Include a quote and state the author’s availability for interviews. Offer to send a copy of the book, either in hard copy or PDF. Have the press release proofed before it goes out.

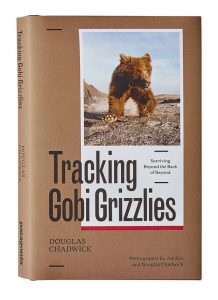

Tracking Gobi Grizzlies

Tracking Gobi Grizzlies by Douglas Chadwick

When pitching

Tracking Gobi Grizzlies by Douglas Chadwick, published by Patagonia, PR by the Book senior publicist Elena Meredith approached four media segments: environmental media, wildlife conservation media, outdoors/adventure media, and media with proximity to grizzly habitat. The book features the world’s rarest bears, a group of two to three dozen grizzlies that reside in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. Climate change and the status of this endangered species were the hard news angles Meredith pitched.

When pitching

Tightwads on the Loose and Sea Trials, published by her own Salsa Press, author Wendy Hinman cast her nets near and far. She sent press releases emphasizing local connections to places she’d lived and drawing attention to scheduled book events. “I focused my energy where I expected the highest chance of success, starting small and then building on that,” she explains.

Hinman says she approached the stories from various angles, tailoring them to fit the publication she was pitching. She thought of what might intrigue someone who knew nothing about the story—what made it unique as well as the educational or entertainment value to the reader. To make the story more vivid and relatable, she included visuals and created catchy headlines. “Be personable and genuine,” she advises. “Create a win-win scenario.”

Her efforts garnered coverage in a college paper and a TV station from her alma mater, the University of Michigan. By pitching to NPR affiliates, she also got interviews that aired on several stations. Her story was featured on the front page of several newspapers, and a national sailing magazine responded to her pitch by publishing the opening chapter of her second book.

Katy Bowman of Propriometrics Press secured the sort of coverage publishers dream of: Along with co-authors Joan Virginia Allen, Shelah Wilgus, Joyce Faber, and Lora Woods, she and their book

Dynamic Aging were featured in a four-and-a-half minute spot on the Today Show in March 2017, a month after the book came out.

“Our pitch came about organically,” Bowman explains. “I was already in contact with Maria Shriver's team regarding the Women's Alzheimer's Movement. They mentioned an item they were preparing for

Today on super-agers, so I mentioned my septuagenarian co-authors.”

Next came what Bowman calls “a bit of a scramble” as her “very small team” worked to generate a pitch package to convince producers that the Today Show audience would want to know about four septuagenarians who hike barefoot and climb trees, moving better and younger than they had a decade earlier.

“We pulled together some great photos of my co-authors in action so the producers could start to visualize the story they'd eventually tell, and we worked hard to encapsulate the message of our book in a narrative the producers would find easy to digest and compelling to share,” Bowman says. “We made the package beautiful to look at, easy to read, and with a story already coming into view.”

Networking is the best way to secure major media coverage, Filipowicz notes. “Unless you personally know Savannah Guthrie, I don’t recommend trying to Facebook message her or calling NBC in New York City and asking for her,” she explains. National anchors are “besieged by viewers,” she says, and they’re often not the ones who decide which stories get aired.

Results

No matter how well-executed, not every pitch results in coverage, nor does all coverage result in blockbusting sales.

“I’ve pitched books and my authors have nabbed appearances on major market television programs,” Colvin says. “By the same token, a few years ago,

Redbook magazine did a feature article on a nonfiction book I wrote. The magazine had a readership of 5 million. It was a great media placement. Did it sell books? No. There was hardly a blip in sales.”

On the other hand, Bowman’s

Today Show coverage yielded both immediate and long-term results. “Our book became a bestseller right away, reaching the No. 2 spot overall on Amazon the day the show aired, and staying in the top 10 until the middle of the following week,” she explains, adding that sales for the book continue to be “incredibly strong.”

Meredith’s efforts garnered wide-ranging coverage. Sierra.org (a publication of The Sierra Club), Yale Climate Connections, Montana Public Radio, Mongabay.org, Shelf Awareness, and

Foreword Reviews were among the media that covered the story. The furthest reach, Meredith says, came from Living on Earth, a weekly environmental news program distributed by Public Radio International and syndicated on NPR stations, also airing as a podcast. Meredith credits the media campaign with helping achieve a stated goal of the publisher—raising tens of thousands of dollars in donations for The Gobi Bear Project.

Financial benefits aside, media coverage also points readers to book events and websites, where Filipowicz advises publishers to incorporate media links. And media coverage begets more media coverage.

“Keep building on earlier efforts,” Hinman advises. “They can snowball.” The stories and interviews featuring her books led to more interviews as well as requests for presentations. And when the current news turns to shipwrecks or pirates or sea rescues, Hinman says reporters now come to her for comment.

Author Wendy Hinman poses with her books,

Tightwads on the Loose and

Sea Trials

Through press coverage, authors and publishers can also share potentially life-changing expertise, even if the tie-in is to a conflict or tragedy. “If you have a book and a career that make you an expert and you genuinely want to help, don’t be afraid to put yourself out there in the news media,” Filipowicz says.

Join the Conversation

As Meredith points out, making news is about joining the conversation. “Gone are the days of editors and producers looking through their stack of galleys for their news of the day,” Meredith says. “They have to serve their audience by joining in the current discussion taking place.”

To join the discussion, savvy publishers pitch strategically, focusing on what journalists want and need to satisfy their audience. By attending to the news values of importance or significance, prominence, conflict, human interest, time, and proximity, publishers show why their books deserve to make news.

Co-founder of 49 Writers and founder of the author co-op Running Fox Books, Deb Vanasse is the author of 17 books. Among her most recent are the novel Cold Spell

and a biography, Wealth Woman: Kate Carmack and the Klondike Race for Gold.

She also works as a freelance editor.

The 6 News Values

Terry Filipowicz started writing for a community newspaper during high school in a Sacramento, California, suburb. “I dreamed of being the next Woodward and Bernstein,” she says. “Or at least I thought I would be able to wear a fedora and trench coat as a hardcore newspaper reporter.”

Then a television news producer visited one of her college classes and hired Filipowicz as a temporary worker to help with the election news coverage. “I ended up working every election for two years until the news director—the boss of the newsroom—called me and offered me an entry-level job,” she says.

Her work at the Sacramento CBS TV affiliate included several years as executive producer, producer, and writer. She also worked as a supervising producer, producer, and writer for the NBC TV affiliate in Tucson, Arizona. “TV ended up a better fit for me over newspapers,” she says. “I like the lights, camera, action as well as the journalism aspects. I move fast and talk fast.”

Filipowicz moved from TV news to publishing in 2013, joining Great Potential Press as vice president, overseeing communications and production. Drawing on her experience in public relations and communications, she also teaches college-level journalism, communication, digital arts, and technical writing.

“Regarding books and authors, what constitutes news is the same as it is for any other story,” Filipowicz says. In her words, these are the news values journalists look for:

- Importance or significance to a story. For a story to be important or significant, it should have a meaningful impact on a meaningful percentage of the audience.

- Prominence. Some people make news no matter what they do, such as British royalty.

- Conflict. Literally, this could be a conflict like war. But it’s also a conflict over ideas like abortion, a school board race, or whether to allow a Walmart in a town.

- Human interest. Some stories are just inherently interesting. In Tucson, the local newspaper looked into a woman’s struggle and triumphs after a car hit her while she was helping a stranded motorist move his car off the road. The crash caused the loss of both legs. Her spine and head had to be surgically reattached. The story was human interest.

- Time. Think of this as timeliness. A story is most newsworthy when it happens. I always said to my newsroom colleagues it’s called “news” not “olds.”

- Proximity. Geographically, the closer a story is to the audience, the easier it is for the story to be considered newsworthy.